Published: May 21, 2012

Spoon boy: Do not try and bend the spoon. That’s impossible. Instead, only try to realize the truth.

Neo: What truth?

Spoon boy: There is no spoon.

Neo: There is no spoon?

Spoon boy: Then you’ll see, that it is not the spoon that bends; it is only yourself.

“Just because there is a UX Strategy group on LinkedIn…, that doesn’t make UX strategy real in the same way that other disciplines and roles—for example, information architecture—are real.”

- “Boxes and Arrows attempts to explain what a UX Strategist is, leaves me more skeptical of the title than ever.” (@ryanvarick)

- “I thought we decided there was no such thing as UX Strategy…and that UX was strategy??” (@hollykennedy13)

- “This UX Strategist role [“What Does a UX Strategist Do?”] should be a skill of a PO [Product Owner] or agile PM.” (@alexhorre)

I thought about what they said and came to the conclusion that they were right. In fact, there is no such thing as UX strategy. Just because there is a UX Strategy group on LinkedIn with over 2500 members and a UX strategy conference in the planning stages, that doesn’t make UX strategy real in the same way that other disciplines and roles—for example, information architecture—are real.

Making UX Strategy Real

“UX strategy … is still very much a practice and a role whose impact we can recognize more in its absence than in its presence….”

But I remember when information architecture wasn’t real either—outside a few early visionary agencies like Clement Mok’s Studio Archetype. It took thousands of projects and millions of project dollars before client partners began to say, “It’s critical that we staff an expert information architect on this project.” UX strategy is in a similar phase now: a few visionaries, a few experts, some digital buzz. It is still very much a practice and a role whose impact we can recognize more in its absence than in its presence—much like information architecture in the 1990’s, when the lack of an information architect could cause the design of a complex site or application to become convoluted, interactive spaghetti.

It is the absence of UX strategy that is, in fact, making it real. The absence of UX strategy in a range of situations is driving UX professionals to bring it into reality by embracing it as our professional focus, producing new work products, and establishing new consulting practices. Agencies like Foolproof in the UK and Retail UX in the USA are pushing hard to make it real, but it’s still relatively rare for organizations to give UX strategy an established place in their budget, resourcing, and project plans.

Sound like nonsense? Consider the following scenarios, which represent real situations interactive agencies and design teams all over the world have encountered.

User Experience Design by Committee

“Organizations feel the absence of UX strategy when one of the committee members … presents best-in-class design work from competitors alongside what the committee has produced….”

Large organizations are seemingly held together by meetings. Meetings in the morning, at midday, in the afternoon, and in the evening. Meetings during meal times. Meetings within meetings. So, it’s not strange that such organizations would want to meet to determine the design direction for a site, application, or product. The result is design by committee.

In such scenarios, organizations feel the absence of UX strategy when one of the committee members gets up his courage and presents best-in-class design work from competitors alongside what the committee has produced to deliver the same feature set. How could the competition have advanced so far while we’ve stayed within our safe boundaries—where we’ve been for years? Hasn’t anyone been keeping track of where the competition was heading?

User Experience Design by Executive Fiat

“The result is … a single, absolute gating of all design ideas.”

Similar to design by committee is the situation in which a design team’s work gets approved or rejected by a single executive. Consider a hypothetical situation with an executive that I’ll call Brooke. Team members ask, “Has Brooke seen this yet?” “Does Brooke know?” “What did Brooke say?” Brooke represents just one of a thousand faces, but the result is the same. A single, absolute gating of all design ideas. The benefit of such an arrangement is that there is no ambiguity about how decisions will get made or who will make them. The downside is that design can never go beyond Brooke’s vision. Seem far-fetched? Not to those of us who have lived it.

Team members in such a scenario feel the absence of UX strategy when they question how all decisions can possibly rest with one person. Doesn’t someone in leadership realize Brooke’s limitations? Can’t someone prove to them that the work we are producing is less than it could be? Can’t someone demonstrate that we could be accomplishing a lot more than we are?

User Experience Design as Incremental Improvement

“A/B testing is both a boon and a curse. … It is a curse because the new designs that get tested must necessarily be very similar to the design for the current site.”

A/B testing is both a boon and a curse. It’s a boon because it gives a very clear indication of which of two designs has, for example, a higher conversion rate on a live Web site. It is a curse because the new designs that get tested must necessarily be very similar to the design for the current site. If it isn’t, the team won’t be able to discern which of the differences caused an effect. This is, of course, where multivariate testing comes in. But even in multivariate testing, there has to be a clearly defined, limited set of design differences in order to draw definitive conclusions about what is causing the results.

A business strategist in such a scenario is feeling the absence of UX strategy when he asks about the potential market value of solutions that are vastly different from what is currently in place. (This actually happened on a project in which I was involved.) “Maybe it’s not a question of improving what we have,” she said,“ but of thinking of something new that meets needs our customers aren’t yet aware a UX design could meet.” Foundational UX research that explores new behaviors or new technologies is a completely different—and much more unpredictable—sort of investigation than testing fully formed design solutions.

User Experience Design as the Big D

“In a User Experience group with a big D designer at the helm, the elegance and originality of a product’s visual impact trumps all other considerations.”

True designers love great design. It sounds obvious, but you can see it in the glasses they wear, the pen case they carry, the desk lamp they use, the sketchbooks they write and draw in, and the pictures they have on their cube walls. They live, sleep, and breathe design. The big D.

In a User Experience group with a big D designer at the helm, the elegance and originality of a product’s visual impact trumps all other considerations. Such leaders understand the importance of usability and meeting user needs. But their thinking and decisions are not weighted toward factors that are outside the province of what they consider exceptional design.

UX strategy’s absence is felt in this scenario when the Manager of Web Analytics posts graphs and charts on the department walls showing the relative monetary value of every design component that has been released to customers for the past three years. At the all-hands meeting, she asks, “How are we evaluating the market value of our user experience designs when they are still in the concept phase?”

User Experience Design as Debate Team

“When someone stands up and asks, “What data do you have that supports what you’re saying?” UX strategy’s absence is felt.”

We’ve all been there. Passionate, endless debate about what a product, site, or application should be. The most convincing orator gets support from others on the team and carries the day. The most passionate person may, in fact, be right about his or her position. But somehow, that person’s opinion always wins the day. As with Mad Money’s Jim Cramer, it’s very difficult to get a bead on how right or how wrong he is. Nevertheless, this person’s assertions are compelling, and he delivers them with such passion that he must be right. Right?

In this scenario, when someone stands up and asks, “What data do you have that supports what you’re saying?” UX strategy’s absence is felt. Standing up to someone’s passion like this has impact only if someonedoes have evidence that indicates one design direction would have more success than another. Such evidence is one of the basic ingredients of UX strategy.

User Experience Design as Lean Agile Production Line

“There is an inherent vested interest in pushing forward user experience designs that are predictable, quick to produce, and easy to develop.”

For the record, I am fully on board with agile UX. The credibility of the leaders of the agile UX movement is well established. Nearly every company that my team and I consult for is at some stage of adopting agile methodology. But whether it’s agile, RUP (Rational Unified Process), or whatever is next in terms of developer-led, design-production approaches, there is an inherent vested interest in pushing forward UX designs that are predictable, quick to produce, and easy to develop. This can lead to sprints that are front-loaded with quick-and-easy features, while interactions that are more complex—or require data, experimentation, or expertise that developers don’t have—may get relegated to the backlog. Once in the backlog bin, visionary user experiences often, unfortunately, get the same treatment as Social Security statements from the government: they’re important somehow, but not immediately relevant.

When the product group gets a new VP who asks a business analyst to calculate the relative market value of what we’re producing versus what’s in the backlog, he’s feeling UX strategy’s absence.

A few months ago, my team and I started providing an agile-friendly usability testing service, offering studies that we time and execute to fit into sprints. So I’m fully on board with agile, but I see a gap that UX strategy can fill to provide long-term value and sustainable competitive advantage.

The Representation of UX Strategy Doesn’t Make It Real

“How will the universally felt absence of UX strategy in design scenarios finally make it real?”

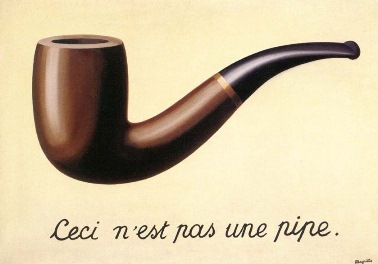

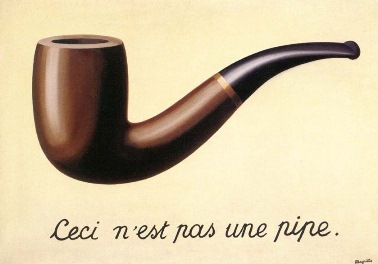

Having a LinkedIn group and a conference called UX Strategydoesn’t make UX strategy real. Having a column on UXmatterscalled UX Strategy doesn’t make it real. In fact, these are just representations—much like Magritte’s painting of a pipe that proclaimed in French, “This is not a pipe,” shown in Figure 1. How will the universally felt absence of UX strategy in design scenarios finally make it real?

Figure 1—Ceci n’est pas une pipe, a painting by Magritte

The following are some examples of conditions that will indicate that UX strategy is, indeed, a real thing rather than just a representation:

- projects that staff UX strategists as a formal, required role that consistently produces well-defined deliverables

- visionary agencies and clients who routinely include UX strategy in their project’s Gantt charts

- staffing specialists who say, “Where are we going to find a UX strategist for this key project?”

- SOWs (Statements of Work) that mention UX strategy and a consistent set of deliverables

- a track in interaction design finishing schools called UX Strategy

- requirements in UX strategist job listings that include relatively similar bullet points across similar ads

- parents and family members overheard at parties saying, “She’s a UX strategist. It’s a pretty cool job.” (Well, in San Francisco, maybe.)

What Does All of This Mean?

“We’re assigning much meaning to the word UX strategy.”

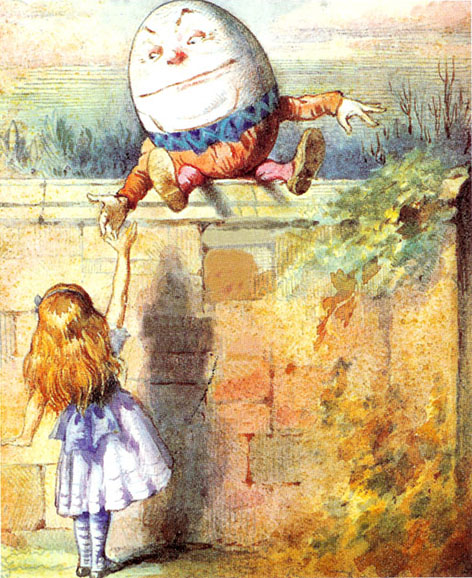

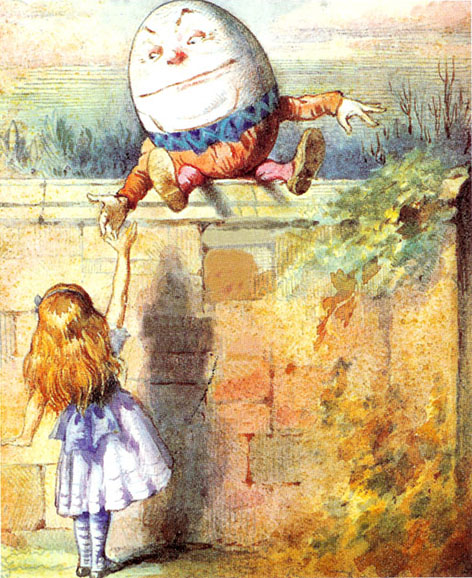

“Would you tell me please,” said Alice, “what that means?”

“Now you talk like a reasonable child,” said Humpty Dumpty, looking very much pleased. “I meant by ‘impenetrability’ that we’ve had enough of that subject, and it would be just as well if you’d mention what you mean to do next, as I suppose you don’t mean to stop here all the rest of your life.”

“That’s a great deal to make one word mean,” Alice said in a thoughtful tone.

“When I make a word do a lot of work like that,” said Humpty Dumpty, “I always pay it extra.”

From Through the Looking Glass by Lewis Carroll

Similar to Humpty Dumpty, shown with Alice in Figure 2, we’re assigning much meaning to the word UX strategy.

Figure 2—Alice and Humpty Dumpty

So, what does the term UX strategy mean? At the moment, it seems to mean whatever the person talking about it says it means. I plan to use my column UX Strategy, the UX Strategy and Planning group on LinkedIn, and the UX Strategy Conference in 2013 to help shape a more consistent vision of UX strategy. But these are only representations.

I also plan to bend my professional practice and engagements in the direction of UX strategy, whenever possible including the activities and deliverables that I described in “

7 Ingredients of a Successful UX Strategy.” The timeframe in which UX strategy will become a real practice and a well-defined role is up to the people who are formulating project plans, writing SOWs, publishing job descriptions, and staffing projects.

Conclusion

“The felt absence of UX strategy indicates that it urgently needs to become a reality.”

In the minds of many UX professionals—at the levels of both members of UX teams and UX executives—there is no such thing as UX strategy. But based on the scenarios that I’ve described in this column—all of which I’ve taken from real-life situations—the felt absence of UX strategy indicates that it urgently needs to become a reality.